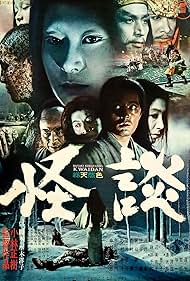

A collection of four Japanese folk tales with supernatural themes.A collection of four Japanese folk tales with supernatural themes.A collection of four Japanese folk tales with supernatural themes.

- Director

- Writers

- Stars

- Nominated for 1 Oscar

- 5 wins & 2 nominations total

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Featured reviews

The words "beautiful", "lyrical" and "evocative" aren't ones that you would normally attribute to a horror movie, but they are precisely the ones that best describe Kwaidan, a quintet of Samurai Gothics based (interestingly enough) on the writings of an American author by the name of Lafcadio Hearn. Shot in gorgeous, sumptuous color way back in 1964 by director Masaki Kobayashi, Kwaidan is an unusual, unique and quite extraordinary entry in the old horror anthology genre best represented by 1945's Dead of Night and Milton Subotsky's Amicus anthology series (i.e. Dr. Terror's House of Horrors, Tales From the Crypt & Asylum).

Kwaidan differentiates itself from the pack in a number of significant ways. To begin with, all of the episodes eschew the usual O. Henry "twist" endings and deliberately telegraph their punches, case in point being "Hoichi the Earless", which gives away its climax with its very title! This film is also missing the compulsory "wrap-around" story normally employed by anthology films to tie all the stories together, and the horror elements are far more low-key than most horror aficianados are used to. Kwaidan is far less concerned with springing shocks and fraying nerves than it is in exploring the whirlwind of conflicting emotions that swirl in the dark night of the human soul.

"The Black Hair" is the tale of an impoverished samurai who abandons his loyal and loving wife to marry the daughter of a wealthy lord in another province, only to discover many years later that he is still in love with his first spouse. He returns to their decaying old house to find her exactly as he left her, affectionate and forgiving as could be. You know something in this household just ain't right. "The Woman in the Snow" concerns an apprentice woodcutter who encounters an eerily beautiful female ice-vampire - called a "Yuki-Onna - who spares his life on the condition that he never tell a soul about their encounter. (If you saw the last episode of the flaccid Tales From the Darkside movie, on which this was based, you have an idea of how this one ends).

"Hoichi the Earless", easily the most powerful of the bunch, regards a blind biwa (a stringed instrument resembling a guitar) player renowned for his moving rendition of the tragic tale of the battle between the Genji and Heiki clans. Each night he is summoned to the nearby graveyard to chant the epic tale for the ghosts of the warriors who fell in that battle, duped by the spirits into believing that he's performing in the home of a wealthy lord. When Hoichi disocvers that he has been decieved by the dead and refuses to perform for them again, the ghosts exact a terrible revenge.

A note of warning to those deterred by long foreign films: this shimmering jewel in Japanese cinema's crown clocks in at nearly three hours of length and is, of course, fully subtitled. Visually bold, rich and color and texture, and atmospherically photographed with a spine-tingling elegance, I can't guarantee that you'll like Kwaidan, but I think that I can safely assure you'll never forget it. Highly recommended, especially for Japanophiles and those with a taste for high class horror.

Kwaidan differentiates itself from the pack in a number of significant ways. To begin with, all of the episodes eschew the usual O. Henry "twist" endings and deliberately telegraph their punches, case in point being "Hoichi the Earless", which gives away its climax with its very title! This film is also missing the compulsory "wrap-around" story normally employed by anthology films to tie all the stories together, and the horror elements are far more low-key than most horror aficianados are used to. Kwaidan is far less concerned with springing shocks and fraying nerves than it is in exploring the whirlwind of conflicting emotions that swirl in the dark night of the human soul.

"The Black Hair" is the tale of an impoverished samurai who abandons his loyal and loving wife to marry the daughter of a wealthy lord in another province, only to discover many years later that he is still in love with his first spouse. He returns to their decaying old house to find her exactly as he left her, affectionate and forgiving as could be. You know something in this household just ain't right. "The Woman in the Snow" concerns an apprentice woodcutter who encounters an eerily beautiful female ice-vampire - called a "Yuki-Onna - who spares his life on the condition that he never tell a soul about their encounter. (If you saw the last episode of the flaccid Tales From the Darkside movie, on which this was based, you have an idea of how this one ends).

"Hoichi the Earless", easily the most powerful of the bunch, regards a blind biwa (a stringed instrument resembling a guitar) player renowned for his moving rendition of the tragic tale of the battle between the Genji and Heiki clans. Each night he is summoned to the nearby graveyard to chant the epic tale for the ghosts of the warriors who fell in that battle, duped by the spirits into believing that he's performing in the home of a wealthy lord. When Hoichi disocvers that he has been decieved by the dead and refuses to perform for them again, the ghosts exact a terrible revenge.

A note of warning to those deterred by long foreign films: this shimmering jewel in Japanese cinema's crown clocks in at nearly three hours of length and is, of course, fully subtitled. Visually bold, rich and color and texture, and atmospherically photographed with a spine-tingling elegance, I can't guarantee that you'll like Kwaidan, but I think that I can safely assure you'll never forget it. Highly recommended, especially for Japanophiles and those with a taste for high class horror.

10OttoVonB

A man returns to his abandoned wife seeking forgiveness and pays for his cruelty. A snow demon and a young man make a pact. A blind priest is summoned by the ghosts of dead warriors to recite the heroic battle that cost them their lives. A samurai is taunted by ghosts in his cup of tea...

Kobayashi's output has been small compared to his contemporaries' (Kurosawa, Ozu...) yet each of his films is an assault on the senses and a visual gem. After unleashing some of Japan's cinematic legends in two of the greatest samurai films ever made (Samurai Rebellion with Toshiro Mifune and the sublime Harakiri with Tatsuya Nakadai), the master moved on to the supernatural with this collection of ghost stories. Filming for the first time in color, Kobayashi wields it like few others before or since, blending spellbinding compositions together and giving us a film of a visual beauty that rivals the best of Kurosawa, Kubrick or Tarkovsky. The eerie feeling of dread is matched only by the film's sheer beauty and power, like watching a moving painting or experiencing a trance.

Kwaidan is not entertaining: it is captivating, bewitching, unique even by it's author's standards. For movie-goers, this is a unique experience. For amateurs of art, it is a feast.

Unmissable!

Kobayashi's output has been small compared to his contemporaries' (Kurosawa, Ozu...) yet each of his films is an assault on the senses and a visual gem. After unleashing some of Japan's cinematic legends in two of the greatest samurai films ever made (Samurai Rebellion with Toshiro Mifune and the sublime Harakiri with Tatsuya Nakadai), the master moved on to the supernatural with this collection of ghost stories. Filming for the first time in color, Kobayashi wields it like few others before or since, blending spellbinding compositions together and giving us a film of a visual beauty that rivals the best of Kurosawa, Kubrick or Tarkovsky. The eerie feeling of dread is matched only by the film's sheer beauty and power, like watching a moving painting or experiencing a trance.

Kwaidan is not entertaining: it is captivating, bewitching, unique even by it's author's standards. For movie-goers, this is a unique experience. For amateurs of art, it is a feast.

Unmissable!

Kwaidan is a four-segment horror anthology but you'd be hard pressed to find one more removed from the typical plastic bats and cobwebs Gothic anthologies of Amicus or Hammer. While it can be billed as a "horror" movie and it deals with the supernatural, it's not really frightening. All four segments are more like traditional Japanese folk legends about ghosts, the kind of spooky stories you could hear an elder narrating to kids around a bonfire in a village near Kyoto or the outskirts of Okinawa. However if "work of art" was a genre, Kwaidan would be among the best it had to offer.

Just two years after the seminal Seppuku which was done in stark black and white with a geometric, well disciplined style, Kobayashi returns with another tour-de-force, this time in extravagant, expressionistic colour. A visual feast proving that in the right hands style can be substance. His camera with its slow tracking shots is like a brush, painting a celluloid canvas with vivid, lush compositions and it comes as no surprise to find out that he had a background in painting. The combination of eerie, supernatural material, the dreamlike atmosphere and the use of colour in lighting and sets reminded me of the great Italian maestro, Mario Bava; although Kwaidan by no means fits in the Gothic horror mold.

Conscious of the folk legend material he's working on, Kobaysi wisely shot the movie in studio sets using large painted backgrounds that look deliberately artificial as much as they look gorgeous. In many ways, it feels like a big stageplay or an elaborate dramatic poem. In that aspect, Kwaidan takes place somewhere between the real and the mythic. A land of some other order.

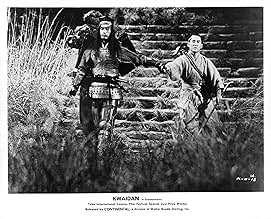

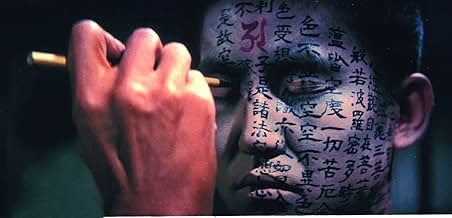

The stories all revolve around ghosts and are as simple and predictable as any spooky story that you might hear as an adult. But they do a great job of providing an eerie skeleton for Kobayashi to hang on his beautiful style. Style over substance one could argue. Isn't that an erroneous statement though? By making the distinction one implies that style is somehow insubstantial to a film, something that couldn't be further from the truth. The use of colour is incredible, the lighting, at times subtle and evocative or wild and expressionistic, the slow tracking shots, long stretches of silence, a body painted with holy text, Tatsuya Nakadai looking calm and happy for a change, Tetsuro Tamba in full plate samurai armor, white ghastly faces, bodies falling in blood-red waters, a painted sunset backdrop, an intelligent play on vague endings, the minimal score, chords echoing from somewhere. Kwaidan proves that style IS substance. A visual feast by all means.

It's really a shame that Kobayashi is not as widely celebrated as Akira Kurosawa. Kwaidan is just another in a series of absolutely brilliant films he did in the 60's. Beautiful, creepy, poetic, atmospheric as hell; it is the work of a master cinematician and one of the best Japanese movies you're likely to see.

Just two years after the seminal Seppuku which was done in stark black and white with a geometric, well disciplined style, Kobayashi returns with another tour-de-force, this time in extravagant, expressionistic colour. A visual feast proving that in the right hands style can be substance. His camera with its slow tracking shots is like a brush, painting a celluloid canvas with vivid, lush compositions and it comes as no surprise to find out that he had a background in painting. The combination of eerie, supernatural material, the dreamlike atmosphere and the use of colour in lighting and sets reminded me of the great Italian maestro, Mario Bava; although Kwaidan by no means fits in the Gothic horror mold.

Conscious of the folk legend material he's working on, Kobaysi wisely shot the movie in studio sets using large painted backgrounds that look deliberately artificial as much as they look gorgeous. In many ways, it feels like a big stageplay or an elaborate dramatic poem. In that aspect, Kwaidan takes place somewhere between the real and the mythic. A land of some other order.

The stories all revolve around ghosts and are as simple and predictable as any spooky story that you might hear as an adult. But they do a great job of providing an eerie skeleton for Kobayashi to hang on his beautiful style. Style over substance one could argue. Isn't that an erroneous statement though? By making the distinction one implies that style is somehow insubstantial to a film, something that couldn't be further from the truth. The use of colour is incredible, the lighting, at times subtle and evocative or wild and expressionistic, the slow tracking shots, long stretches of silence, a body painted with holy text, Tatsuya Nakadai looking calm and happy for a change, Tetsuro Tamba in full plate samurai armor, white ghastly faces, bodies falling in blood-red waters, a painted sunset backdrop, an intelligent play on vague endings, the minimal score, chords echoing from somewhere. Kwaidan proves that style IS substance. A visual feast by all means.

It's really a shame that Kobayashi is not as widely celebrated as Akira Kurosawa. Kwaidan is just another in a series of absolutely brilliant films he did in the 60's. Beautiful, creepy, poetic, atmospheric as hell; it is the work of a master cinematician and one of the best Japanese movies you're likely to see.

There's a good bit of discussion of this film as "horror"; may I suggest that it's horrific in the sense of the ancient Greek tragedies. There's no attempt to coerce your Hollywood-abused adrenals into delivering just one more squirt by means of some in-your-face special effect. In fact, for each of these slowly developed stories, once you've understood the premise, the story will unfold pretty much as you've guessed it must, inexorably, relentlessly. The ghosts aren't there to "spook" us, they're to show us our common human spiritual and emotional failings. The horror of a ghost wife, for instance, isn't that her chains drag noisily across the the hardwood parquet floor, but that we've created her by our insensitivity, our misplaced values, or our betrayals.

The visual style is stupendous! The action takes place in a disappeared, iconic world of classical medieval Japan, perfect, and admitting no trace of the reality of modern times. Overlaid is a European Expressionist color sensibility, with emotionally charged color displacements of sky and skin, as if Hokusai and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner had been working cooperatively on the sets and lighting.

This is a wonderful movie. Please ignore attempts to fit it into some box, some genre. Rather look at it as a mature work of art, which happens to choose old Japanese ghost stories as its starting point.

The visual style is stupendous! The action takes place in a disappeared, iconic world of classical medieval Japan, perfect, and admitting no trace of the reality of modern times. Overlaid is a European Expressionist color sensibility, with emotionally charged color displacements of sky and skin, as if Hokusai and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner had been working cooperatively on the sets and lighting.

This is a wonderful movie. Please ignore attempts to fit it into some box, some genre. Rather look at it as a mature work of art, which happens to choose old Japanese ghost stories as its starting point.

Four old ghost stories, updated in the late 19th Century by the Irish-Greek-America Lafcadio Hearne, then reclaimed by Kobayashi Masaki in the 1960's. This really isn't your regular horror movie to put it mildly - All four stories are told in a highly theatrical manner with deliberately stylized studios and acting. Some of the sets are very beautiful, a quite unique cinema experience.

It is, however, very uneven. The first story, 'the Woman of the Black Hair' is lovely in parts, but the ending disappoints (its different from the Lafcadio Hearne original). The second one, the 'Woman of the Snow' is genuinely very creepy and shocking. The third story, 'Hoichi the Earless' is by far the most impressive, with memorable visuals and music. The last story, 'In a Cup of Tea' is a more conventional 'tales of the unexpected' type story and is a little overlong. Its really a bit of a shaggy dog story, not worthy of the others.

There is no doubt that its a very beautiful movie in parts - some sections are genuinely memorable and will likely stick in your mind for a lot longer than the usual ghost stories. I don't think its as good a movie as some other Japanese horror movies of the period such as Onibaba or Woman of the Dunes (both made two years before this). However, it is fascinating in the little insights it gives to the pleasures of traditional Japanese theater.

It is, however, very uneven. The first story, 'the Woman of the Black Hair' is lovely in parts, but the ending disappoints (its different from the Lafcadio Hearne original). The second one, the 'Woman of the Snow' is genuinely very creepy and shocking. The third story, 'Hoichi the Earless' is by far the most impressive, with memorable visuals and music. The last story, 'In a Cup of Tea' is a more conventional 'tales of the unexpected' type story and is a little overlong. Its really a bit of a shaggy dog story, not worthy of the others.

There is no doubt that its a very beautiful movie in parts - some sections are genuinely memorable and will likely stick in your mind for a lot longer than the usual ghost stories. I don't think its as good a movie as some other Japanese horror movies of the period such as Onibaba or Woman of the Dunes (both made two years before this). However, it is fascinating in the little insights it gives to the pleasures of traditional Japanese theater.

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaThe four vignettes were chosen to represent the four seasons of the year.

- Goofs(at around 2h 25 mins) In the segment "Miminashi Hôichi no hanashi", Donkai says he covered all of Hôichi's body with the sacred writing, but when Hôichi is writhing on the floor after the ghost's attack, his thighs (which in the shots were supposed to be covered by his robe) are visible for a couple of seconds and are clearly unmarked.

- Quotes

Hoichi (segment "Miminashi Hôichi no hanashi"): As long as I live, I'll continue to play the biwa. I'll play with all my soul to mourn those thousands of spirits who burn with bitter hatred.

- Alternate versionsOriginally a four-episode anthology released in Japan at 183 minutes. The USA version removes the second episode, starring Keiko Kishi and Tatsuya Nakadai, in order to shorten the running time to 125 minutes.

- ConnectionsEdited into Catalogue of Ships (2008)

- How long is Kwaidan?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- ¥350,000,000 (estimated)

- Runtime3 hours 3 minutes

- Aspect ratio

- 2.35 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content